The

Clarinet Family

The

Clarinet Family

There are actually a lot different

types of clarinets. The type of clarinet you are probably most

familiar with is the "Bb Clarinet" - this is the clarinet most often

used in bands, jazz and orchestras. If you played clarinet back in

school, this is the instrument you would have played. There are over

ten different kinds of clarinets in the Clarinet Family.

Additionally, for each kind of clarinet there are a number of

different variations in terms of keywork and bore. Let's just say

there are a lot of different types of clarinets.

"Big Clarinets" >

Buddy DeFranco

No

man living has witnessed more jazz history than clarinettist Buddy

DeFranco. Born in 1923, he first played in public at the age of 12.

Working in some of the top swing bands while still a teenager,

DeFranco then contributed to the bebop revolution in New York during

the 1940s. He recorded with Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Oscar

Peterson, Art Tatum and many others. With his mastery of the

harmonic language of modern jazz, his characteristic tone and his

scintillating command of the top register, Buddy's

grit, groove and grace won him 20 Down Beat Polls, 14 Playboy All

Star Awards, seven Metronome All Star Polls, and three Melody Maker

polls.

No

man living has witnessed more jazz history than clarinettist Buddy

DeFranco. Born in 1923, he first played in public at the age of 12.

Working in some of the top swing bands while still a teenager,

DeFranco then contributed to the bebop revolution in New York during

the 1940s. He recorded with Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Oscar

Peterson, Art Tatum and many others. With his mastery of the

harmonic language of modern jazz, his characteristic tone and his

scintillating command of the top register, Buddy's

grit, groove and grace won him 20 Down Beat Polls, 14 Playboy All

Star Awards, seven Metronome All Star Polls, and three Melody Maker

polls.

DeFranco was

the jazz clarinet player of significance during the decades that

followed the mid-century hegemony of Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw.

Now, past the age of eighty, he still plays elegantly. For evidence,

hear his new CD, Cookin’ the Books (Arbors Records, ARCD

19298).

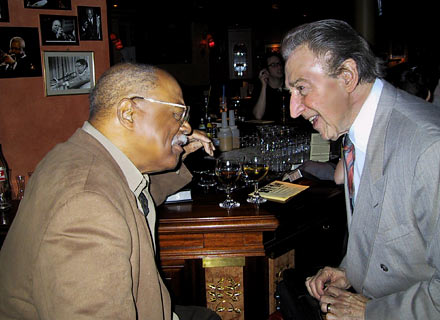

<Clark Terry & Buddy DeFranco

“There are two

approaches to playing jazz. In one area, which is still valid –

don’t misunderstand me – the players believe that too much

practising, or any practising, inhibits you from playing good jazz.

So they don’t like the idea of study, or practice of any of the

fundamentals. Using that approach to jazz are some very well known

players. Pee Wee Russell was a good example. He was not a schooled

player, but he did play a form of jazz, as opposed to Benny Goodman

or Artie Shaw, who obviously had formal training. I’m from the

latter school. I believe that you need as much technique as you can

acquire, in order to say what you are going to say immediately,

extemporaneously.

“You’ve got to learn the formal scales, arpeggios, chords, before

you can go into jazz and execute what you’re thinking. I acquired

the technique from formal training. I was a symphonic clarinettist

before I started playing jazz.”

Have you worked hard at gaining command of the very high notes?

“What started me thinking about playing that high register was

Artie Shaw. He was just fascinating, the way he had control of the

high register. He was unstoppable. Most clarinettists, when they

played high, they played fail-safe music, fail-safe licks. They

would play what they were comfortable with, so that there would be

no trouble. Artie disregarded that. He just played. That’s what I

try to do. In those days you couldn’t get close to Artie or Benny. I

did get close to Benny, but even Benny Goodman, when you brought up

the clarinet, he didn’t want to talk about his secrets.

“Times

have changed. Now it’s very open. You can study so many different

ways. I approve. Unfortunately, it sometimes turns out automatons or

clones, which I don’t approve. Originality is more important than

anything you can do on the instrument. There’s no such thing as

mastering an instrument, but if you want to develop your technique,

all it takes is practice. But you cannot develop a personality by

practising. Somehow, it has to come through from within. The trick

is to bring your personality into your playing. If you are staying

with all those patterns that you cloned, you are not going anywhere.

It’s easy to talk about; it’s not easy to do.”

“Times

have changed. Now it’s very open. You can study so many different

ways. I approve. Unfortunately, it sometimes turns out automatons or

clones, which I don’t approve. Originality is more important than

anything you can do on the instrument. There’s no such thing as

mastering an instrument, but if you want to develop your technique,

all it takes is practice. But you cannot develop a personality by

practising. Somehow, it has to come through from within. The trick

is to bring your personality into your playing. If you are staying

with all those patterns that you cloned, you are not going anywhere.

It’s easy to talk about; it’s not easy to do.”

Nevertheless, Buddy admits that there is a place for fail-safe

playing.

“There’s a trick that I learned from Charlie Parker. That is, to be

so zeroed in on what you’re playing that no matter what is happening

behind you, it doesn’t really matter. Through the years Charlie

Parker has played with some of the worst rhythm players. But when

you hear him, you’re convinced that he’s got a great rhythm section.

He blanks it out. He’s so dominant, so positive."

How do you develop that?

"By listening, observing. It all boils down to the same thing:

fundamentals. I practise the fundamentals every day. The only change

that I made (it’s a question of my ego) is some years ago I wrote a

book – it’s still available – of Hanon exercises. The original Hanon

exercises for the piano are all in C. I decided that a Hanon

exercise for clarinet should be in all keys, so I called it Hand

in Hand with Hanon, and it’s a Hanon exercise in every key. I

added that to my practice. I’m very strict with practice. It’s a

question of being very compulsive."

Does Buddy regard himself as compulsive?

"If you weren’t compulsive, you wouldn’t be a clarinet player."

Buddy DeFranco has

been a Yamaha artist since 1985. He performs on the Yamaha Custom V.

Buddy is one of Yamaha's most notable performing artists. Mr.

DeFranco is one of the most influential jazz artists in history,

winning countless awards and appearing on a multitude of jazz

recordings. He has appeared with Gene Krupa, Tommy Dorsey, and Count

Basie to name a few. At the young age of 80 Buddy remains

imaginative and active as a performer and international clinician.

My Yamaha Custom clarinet "covers all the bases"! It is free

blowing, the intonation top to bottom is quite good, and very even.

It has a full, rich tone, and a very comfortable key mechanism.

Selected

Recordings

Crosscurrents with L. Tristano (1949, Cap. 11060)

Buddy De Franco and Oscar Peterson play George Gershwin

(1954, Verve 314 557 099-2)

Art Tatum-Buddy DeFranco Quartet with Art Tatum (1956, Verve

8229)

Buddy DeFranco Meets the Oscar Peterson Quartet (1985,

Pablo 2310915)

Alan

Barnes

Born

in 1959 in Altrincham, Barnes plays all of the single reeds, and is

a superb clarinettist. His live album, Cannonball, was voted

album of the year in the 2001 British Jazz Awards and he was named

BBC Jazz Instrumentalist of the Year. He now has his own record

label, Woodville Records. Barnes possesses an

in-depth knowledge of jazz history, coupled with a sincere love of

pre-1950s jazz.

Born

in 1959 in Altrincham, Barnes plays all of the single reeds, and is

a superb clarinettist. His live album, Cannonball, was voted

album of the year in the 2001 British Jazz Awards and he was named

BBC Jazz Instrumentalist of the Year. He now has his own record

label, Woodville Records. Barnes possesses an

in-depth knowledge of jazz history, coupled with a sincere love of

pre-1950s jazz.

“The difference between jazz and classical clarinet is that

if you choose to have a jazz career there are so many different ways

you can go. With the classical thing, there’s pretty much an agreed

path. There are sets of exercises and repertoire. But in jazz, with

all of the different sounds, for instance, on the clarinet, you can

go different ways.

"The difference between Sidney Bechet, Johnny Dodds and Artie Shaw

is phenomenal. I’m not sure that any one clarinettist can get all of

those sounds. Maybe Tony Coe could. So I guess that if a student was

interested in playing jazz you’d have to choose more specifically

than just jazz. It would have to be down to individuals, to

clarinettists that enthuse that student.

Listening is absolutely paramount. The first thing I say to any

student who comes to me, before I accept them, is: ‘Who do you

listen to?’ It’s phenomenal to me that certain people don’t listen

to anybody. And they want to be a jazz clarinet player! For

instance, I’ve had tenor students say they haven’t heard Don Weller,

and they haven’t heard Dick Morrisey, or Bobby Wellins. And I think,

if they haven’t heard these people… and they are on the doorstep...”

Alan shrugs, and smiles.

“Often people don’t realise that’s what music is about:

listening. Performing is about listening. In jazz, when you’ve

finished your chorus, you don’t then ignore what everybody else is

doing, because it should change what happens next.

"I would start with Johnny Dodds – with Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five –

in Weary Blues. Anybody of Grade 2 or Grade 3 standard could

probably play the two Johnny Dodds choruses on Weary Blues, a

beautiful solo. You don’t have to have the greatest technique in the

world to play great jazz. Dodds’ sound is probably an acquired taste

for some people, but it’s instantly recognisable, and it’s certainly

full. It’s only two choruses long, so you learn brevity."

Do you recommend that they memorise or transcribe?

“Whichever you want to do. If you can sing it, you’ve learnt it.

There’s also a value in writing it down; you can learn to read by

transcribing. To me, the early jazz players played the clarinet like

a clarinet. And as it went on, you thought – oh, isn’t it amazing

that they can do that on the clarinet?

“In the old days they played clarinetty things. Which is what I

think is the instrument’s strength. So you get Barney Bigard doing

all those odd intervals that would be difficult on the trumpet.

That’s why I don’t really play bebop on the clarinet. I always use

it at a point in the programme where it’s either a ballad, or

something where you can play a clarinet like a clarinet.

“Some of the early clarinettists exploited the problems of the

clarinet, like the three different sounds, instead of trying to make

it smooth from bottom to top. Why not have three different sounds,

as Sidney Bechet did? And then there’s Pee Wee Russell, getting in

all the wheezy throat notes. Jimmy Guiffre is another one. There’s a

man who has obviously got the whole of the musical concept together,

then he chooses to play the clarinet in the low register! I love his

playing.”

Is there a place for practising patterns for jazz?

“I think you’ve got to do some sort of exotic scale practice.

For instance, if Bflatm7flat5 to Eflat7aug#9 comes up, for a bar

each, you’ve got to have practised whatever you think fits that. I

actually get some phrases going on those things. Otherwise, with the

clarinet, and the cross-fingering, when you are improvising, you are

going to end up in all kinds of trouble.”

So, preparation is acceptable?

“There are two schools of thought. Lee Konitz thought that

improvising should be just that. Yet Louis Armstrong played the same

solos night in and night out. I don’t think that stopped it from

being some of the best jazz ever played. Jazz is prepared, but not

totally prepared.”

Clarinet Exponents

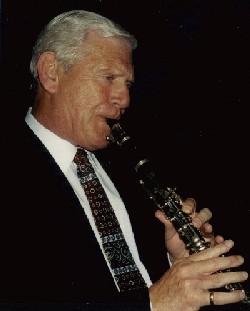

Dave

Shepherd

born London 7

February 1929 clarinet

Dave

Shepherd

born London 7

February 1929 clarinet

Dave became interested in the clarinet at the

age of sixteen after hearing The First English Public Jam Session

recorded 6 November 1941 (the recording featured Harry Parry playing

clarinet on I Found A New Baby). Dave was taught to play the

clarinet by Bernie Izen, Freddy Randall's clarinet player at the

time. At eighteen he was conscripted to the army for national

service and posted to the British Forces Radio Network Quartet in

Hamburg, Germany. During this time he received lessons for the two

years of service from the principal clarinettist of the Hamburg

State Orchestra.

After leaving the army in 1949 he turned professional and in 1951

joined the Joe Daniels' Hot Shots (which later became the Joe

Daniels Jazz Group). Dave joined the Freddy Randall Band in 1953,

played with the band until early 1955. During this time he played on

two LPs for the American market at the IBC Studios in London circ.

1953 (Salute to Benny Goodman for the solitaire Manhattan Label,

with the Teddy Foster's Big Band and also with his quartet). Then in

1955 Dave decided to go to America, playing in New York with many of

the best U.S. musicians at that time.

He returned to the UK in late 1956, toured with Norman Granz Jazz at

the Philharmonic, and worked with the Oscar Peterson Trio, Ella

Fitzgerald, Stan Getz, Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Roy

Eldridge, Sonny Stitt, Lou Levy, Gus Johnson and the Dill Jones

Quartet to name a few. During this time he formed the Dave Shepherd

Quintet and began broadcasting on BBC Radio as well as working with

the The Jazz Today Unit and touring with Gerry Mulligan, Billie

Holiday and Mary Lou Williams.

In 1960 Dave rejoined the Freddy Randall Band until the end of the

Trad Boom, and then commenced a series of tours with Teddy Wilson in

the UK, Europe and South Africa.

During the middle of 1972 the Northern Arts Council approached him

to join a band called Britain's Greatest Jazz Band. The band was

formed from a nominated group of British jazz musicians for a tour

in the far north of England from 28 July - 1 August 1972. From the

tour an LP was recorded. After the tour the band decided to remain

together and called themselves the Freddy Randall/Dave Shepherd Jazz

All Stars, which played several concerts and numerous BBC Radio

broadcasts. LPs were recorded for Black Lion and the band

represented the UK in the Alan Bates Salute to Swing event at the

Montreux Festival in July 1973. An LP was also recorded with Teddy

Wilson at this event.

After Randall disbanded, Dave played with American jazz legends such

as Bud Freeman, Yank Lawson, Ruby Braff, Wild Bill Davison and

Barney Kessel. In the 1980s he toured with the Benny Goodman Alumni

Sextet (Pete Appleyard, Barney Kessel, Bobby Rosengarden, Major

Holley and Derek Smith) before becoming leader of the Pizza Express

All-Stars in 1981. Dave toured New Zealand in 1986, and appears

regularly in various venues/jazz clubs all over the UK with and

without the quintet.

Jazz festivals he has played include; Montreux 1973, Edinburgh

throughout the 1980s, Cork, The Hague, Dresden, Nice, Glasgow, Isle

of Man, Jersey and Chichester.

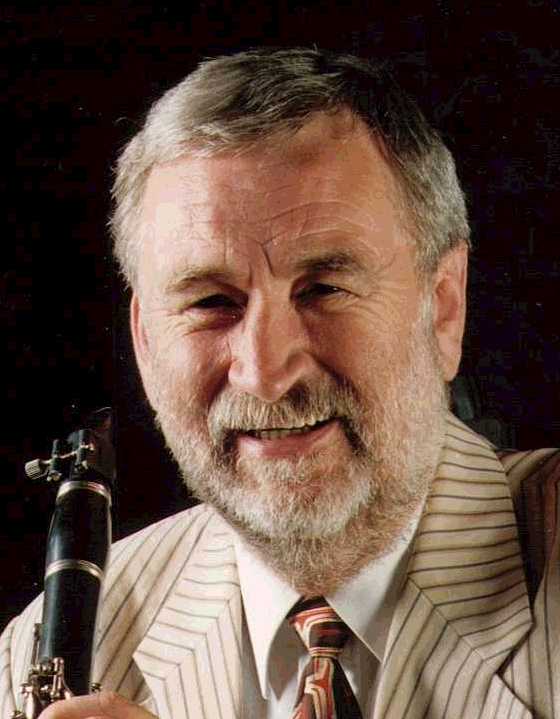

Chris

Walker - born

in 1939 and took up playing clarinet at the age of 15, having been a

member of the school recorder band since he was 11. After leaving

school he played regularly around the London jazz scene, as a member

of The Freddy Shaw Jazzmen, before becoming a professional musician

with The London City Stompers and, later, with the Mike Daniels Big

Band and Colin Kingwell’s Jazz Bandits. Chris moved to Hampshire in

1969 and, since then, he has worked with most of the local jazz

personalities, was a member of The Real Ale & Thunder Band for 18

years, and has run his own highly successful 5-piece ‘Swingtet’ for

the last 15 years. Whilst with the Real Ale & Thunder Band, Chris

was, in 1987, the musical director for an historic BBC “Songs of

Praise” from The Maltings in Farnham and, since 1980; he has

produced a series of music and information based jazz programmes for

BBC Local radio all across the South. Currently

he can be heard, every Sunday, presenting the Jazz hour between 4pm

and 5pm on BBC Radio Solent and on BBC Southern Counties Radio. He

also produces and presents the complete jazz diary for the area on

Tuesdays and Fridays on BBC Solent. In addition to managing and

fronting ‘The Chris Walker Swingtet’, Chris has, for Messrs P&O

Cruises, co-ordinated Jazz Themes aboard 7 highly appraised cruises

on both Canberra and Oriana. He also acts as jazz advisor to

Portsmouth City Council for their Jazz Day every summer on Southsea

Sea front, helped set up the original concept for the Chichester

Real Ale & Jazz Festival, and now, annually arranges and hosts the

jazz programme for the Reading Real Ale & Jazz Festival every July.

Chris

Walker - born

in 1939 and took up playing clarinet at the age of 15, having been a

member of the school recorder band since he was 11. After leaving

school he played regularly around the London jazz scene, as a member

of The Freddy Shaw Jazzmen, before becoming a professional musician

with The London City Stompers and, later, with the Mike Daniels Big

Band and Colin Kingwell’s Jazz Bandits. Chris moved to Hampshire in

1969 and, since then, he has worked with most of the local jazz

personalities, was a member of The Real Ale & Thunder Band for 18

years, and has run his own highly successful 5-piece ‘Swingtet’ for

the last 15 years. Whilst with the Real Ale & Thunder Band, Chris

was, in 1987, the musical director for an historic BBC “Songs of

Praise” from The Maltings in Farnham and, since 1980; he has

produced a series of music and information based jazz programmes for

BBC Local radio all across the South. Currently

he can be heard, every Sunday, presenting the Jazz hour between 4pm

and 5pm on BBC Radio Solent and on BBC Southern Counties Radio. He

also produces and presents the complete jazz diary for the area on

Tuesdays and Fridays on BBC Solent. In addition to managing and

fronting ‘The Chris Walker Swingtet’, Chris has, for Messrs P&O

Cruises, co-ordinated Jazz Themes aboard 7 highly appraised cruises

on both Canberra and Oriana. He also acts as jazz advisor to

Portsmouth City Council for their Jazz Day every summer on Southsea

Sea front, helped set up the original concept for the Chichester

Real Ale & Jazz Festival, and now, annually arranges and hosts the

jazz programme for the Reading Real Ale & Jazz Festival every July.

Mark

began his musical training by earning a degree in music performance

at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music. He moved to London to study

on the postgraduate jazz course at the Guildhall School of Music

after winning the Young Jazz Player of the Year Competition in 1991.

Since leaving college Mark has worked in a wide range of musical

settings including classical work and shows but is most at home in

the jazz world. He has played in all of London’s top jazz venues and

at jazz festivals up and down the country. A recent highlight was a

week’s engagement at Ronnie Scott’s with the John Critchinson

Quartet opposite the Mingus Big Band. Mark’s own group

features his clarinet and tenor with the brilliant guitar playing of

Colin Oxley and is featured on his highly-rated CDs “I Won’t Dance”

and the brand new “How My Heart Sings”. Mark is a member of

the Back To Basie Orchestra and the John Wilson Orchestra. He also

enjoys appearing in a two-tenor “Al and Zoot” group with Jim

Tomlinson and a two-clarinet “Benny” quintet with Julian Stringle.

Mark was the featured soloist in a gala “Tribute to Artie Shaw”

concert in Dublin’s National Concert Hall in January 2006. A

hand-picked 26 piece orchestra accompanied Mark in scintillating

performances of original Shaw arrangements including the infamous

Interlude in Bb for clarinet and string quartet and Shaw’s virtuoso

Concerto for Clarinet .The concert was such a great success that

Mark was immediately invited back to perform a Benny Goodman

programme in April 2007 and to reprise the Artie Shaw with Strings

Concert in October 2007.

Mark

began his musical training by earning a degree in music performance

at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music. He moved to London to study

on the postgraduate jazz course at the Guildhall School of Music

after winning the Young Jazz Player of the Year Competition in 1991.

Since leaving college Mark has worked in a wide range of musical

settings including classical work and shows but is most at home in

the jazz world. He has played in all of London’s top jazz venues and

at jazz festivals up and down the country. A recent highlight was a

week’s engagement at Ronnie Scott’s with the John Critchinson

Quartet opposite the Mingus Big Band. Mark’s own group

features his clarinet and tenor with the brilliant guitar playing of

Colin Oxley and is featured on his highly-rated CDs “I Won’t Dance”

and the brand new “How My Heart Sings”. Mark is a member of

the Back To Basie Orchestra and the John Wilson Orchestra. He also

enjoys appearing in a two-tenor “Al and Zoot” group with Jim

Tomlinson and a two-clarinet “Benny” quintet with Julian Stringle.

Mark was the featured soloist in a gala “Tribute to Artie Shaw”

concert in Dublin’s National Concert Hall in January 2006. A

hand-picked 26 piece orchestra accompanied Mark in scintillating

performances of original Shaw arrangements including the infamous

Interlude in Bb for clarinet and string quartet and Shaw’s virtuoso

Concerto for Clarinet .The concert was such a great success that

Mark was immediately invited back to perform a Benny Goodman

programme in April 2007 and to reprise the Artie Shaw with Strings

Concert in October 2007.

The

Chiltern Hundreds Jazz

Festival - yes it is possible - given Arts Grants and Corporate support.

There are sufficient venues both in the Town Centres and the surrounding Villages

to create a Major Annual Event (even Bicester organises one) - If you are

interested then declare here in what capacity you are prepared to assist.

The

Chiltern Hundreds Jazz

Festival - yes it is possible - given Arts Grants and Corporate support.

There are sufficient venues both in the Town Centres and the surrounding Villages

to create a Major Annual Event (even Bicester organises one) - If you are

interested then declare here in what capacity you are prepared to assist.