|

| |

UK Jazz Piano Pioneers

Nottingham

National Jazz Piano Competition - Judges

1.

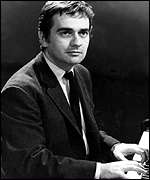

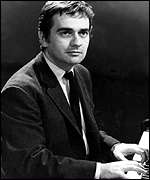

Dudley

Moore

Dudley

Stuart John Moore was born in Dagenham, East London on April

19th, 1935. He was taught the piano by his parents when just

eight and took up the violin aged eleven. Young Dudley also

attended the Guildhall School Of Music every Saturday

morning, learning the history and appreciation of music as

well as violin lessons. Whilst singing in the choir in his

local Dagenham church, he was persuaded to play the church

organ and further persuaded to apply for an organ

scholarship to study music at University. Dudley was

successful, attained the scholarship and entered Oxford

University, graduating aged 22 with BA degrees in both Music

and Composition from Magdalen College. Dudley

Stuart John Moore was born in Dagenham, East London on April

19th, 1935. He was taught the piano by his parents when just

eight and took up the violin aged eleven. Young Dudley also

attended the Guildhall School Of Music every Saturday

morning, learning the history and appreciation of music as

well as violin lessons. Whilst singing in the choir in his

local Dagenham church, he was persuaded to play the church

organ and further persuaded to apply for an organ

scholarship to study music at University. Dudley was

successful, attained the scholarship and entered Oxford

University, graduating aged 22 with BA degrees in both Music

and Composition from Magdalen College.

After graduation, he

left Oxford in 1958 as an accomplished jazz pianist,

performing with Johnny Dankworth and touring the US for a

year with the Vic Lewis band.

Dudley played jazz piano at

various locations whilst also appearing in the comedy revue

“Beyond The Fringe” with Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller and

Alan Bennett. In 1961 Peter Cook bought a former strip joint

in Soho and opened The Establishment Club – a cabaret club

with Dudley playing jazz in the cellar alongside bassist

Pete McGurk and drummer Chris Karan… and so the

Dudley Moore

Trio was born. Dudley's jazz style was influenced in his

teens by his idols Erroll Garner and Oscar Peterson, who

inspired him to stretch his style.

Moore died at his New Jersey home on 27/03/02, after the

degenerative progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) which

plagued the final years of his life led to pneumonia.

2. Terry

Shannon

At a time when few British jazzmen had even a feint whiff of

authenticity about them, Terry Shannon

stood out, despite being within two thousand miles from New York's

Birdland. Like his predecessors, Shannon was a self-taught talent,

relying more on what could be gleaned from records than on any academic

training. This is all the more surprising when one considers how

harmonically erudite his playing was.

Shannon entered the music business with some reluctance, abandoning a

good day job to join the quartet of clarinettist Vic Ash and to work on

record with musicians such as trumpeter Dizzy Reece and saxophonist

Ronnie Scott. One of Shannon's earliest recordings was the 10" Tempo

album Dizzy Blows Bird on which he accompanied Dizzy Reece

through a programme of numbers associated with Charlie Parker (A New

Star).

The

two takes of Parker's blues Bluebird contain superlative early

Shannon; he already displays the virtues that would lead many of

Britain's modernists to cite him as their favourite pianist, the

grooving sense of time, the assertive but never boisterous

accompaniment, and solo lines which snake through the chord changes with

a knowing sophistication. Shannon named his favourite pianists as Tommy

Flanagan, Horace Silver, Bud Powell and Sonny Clark, and it is possible

to hear elements of each of those performers in his work at this time,

and also, in the telling economy of his statements and comping, that of

John Lewis. The

two takes of Parker's blues Bluebird contain superlative early

Shannon; he already displays the virtues that would lead many of

Britain's modernists to cite him as their favourite pianist, the

grooving sense of time, the assertive but never boisterous

accompaniment, and solo lines which snake through the chord changes with

a knowing sophistication. Shannon named his favourite pianists as Tommy

Flanagan, Horace Silver, Bud Powell and Sonny Clark, and it is possible

to hear elements of each of those performers in his work at this time,

and also, in the telling economy of his statements and comping, that of

John Lewis. In 1957 Shannon joined the Jazz Couriers led by

Ronnie Scott and

Tubby Hayes, and it is hard to imagine a better context in which to

place his gifts. Like Hayes (who tolerated Shannon's poor sight reading

skills because he admired his playing so much), Shannon was a perfect

synthesiser of the latest jazz trends from America, and yet he never

sounded empty or faceless. His work throughout the four Jazz Couriers

albums (available on several reissues) is that of a master pianist, and

one can cite his tactful comping on After Tea from The

Couriers of Jazz album as an excellent example of his skill as

musical prompt, or his solo on The Serpent (now on the CD Some

Of My Best Friends Are Blues) as an example of his ability to

develop the thread of a solo, or his brief improvisation on My Funny

Valentine (again from the The Couriers of Jazz CD) as an

example of his re-harmonisation of a hackneyed theme.

Hayes was quick to praise Shannon's contribution to the Couriers

music, and when the band split in 1959 Shannon would stay on and spend a

further five years working with Tubby's various groups. This work is

spread across several albums, including Tubby's Groove (included

on The Eighth Wonder), Palladium Jazz Date, Tubbs,

Tubbs' Tours and archive issues such as Tribute to Tubbs,

Live In London Volume 1 and Volume 2 and Night and Day.

Throughout this impressive body of work Shannon emerges as an amazingly

consistent performer, unfazed by Hayes' virtuosity, and even, by dint of

a canny brain and a subtle technique, able to undercut the nominal star.

Blue Hayes from the 1959 Tubby's Groove set is a

masterpiece for Shannon, joining the performance on Blues For Tony

which he recorded with Jamaican saxophonist Wilton "Bogey" Gaynair the

same year (the album Blue Bogey) as evidence of Shannon's genuine

ability to play the blues in a convincing and sincere way.

Frustratingly, Shannon's career began to falter in the late 1960s,

through a combination of the usual jazz vices and bitterness (he was

especially cynical about the lack of cohesive rhythm sections on the

local scene), and by the end of the decade he was almost invisible on

the musical radar. His career since then has been a similarly

inconsistent mix of potential comebacks, dissipation and abstraction,

and despite the efforts of his one time producer at Tempo, Tony Hall, to

get Terry to record again, he has become all but musically silent, an

ignominious shame for a musician who was once central to one of the

finest jazz groups this country has produced.- Simon Spillett

I just came across this and had to e-mail you

We moved to Grimsby in 1987 and had the great pleasure of having Terry

for a neighbour for 5 years.

Having been in group myself and fancying myself as a musician I can't

imagine a more pleasurable way to be proved how wrong I was.

I can only say that sitting in his house, listening to him improvise

hour after hour was just incredible.

I even got to roadie for him at local gigs and once he persuaded me to

accompany him on bass (though in the end I doubt the audience heard me -

but he did).

Just as good was that he and his wife would baby sit with our kids,- who

all loved them both. Last heard he was living in Wragby ( a village nearer to Lincoln) and

still playing with local bands Jazz Eddie - thanks for this contribution from -

David Watson

3.

Eddie Thompson was one of the few

London modernists to successfully steer a profitable course through the

middle ground that lay between artistic congruency and overt

commercialism. Thompson, like George Shearing, had been blind since

childhood, and similarly he shared an ability to put across

sophisticated musical concepts in a manner so effortless and fluid that

they seemed palatable to a wider audience. Thus Thompson could find

himself booked as a variety act or a jazz performer and not have to bend

either way to fit the bill. A sadly unavailable trio album, Piano

Moods, made in 1959 and released on the Ember label, was an early

classic containing an effective cross section of Thompson's musical

world, from the sparkling Red Garland-like dancing figures he sprinkled

above fast themes, to a more sombre and stoic lyricism that presaged the

brooding introspection Bill Evans would come to make his own, as on

Thompson's own composition Three For Three Four. At this time

Thompson's repertoire contained what must surely qualify as one of the

most unusual appropriations of English musical culture into a jazz

settings, a jaunty re-arrangement of Flanagan and Allen's Underneath

the Arches, a performance which on paper might sound improbable but

is actually delightful. Thompson went one better on the now very rare

1958 Vox album London By Night, when he recorded a programme of

songs dedicated to the English capital, including such unlikely fare as

Passport to Pimlico and London Pride.

London was indeed proud of Thompson's talents, and one of his career

highlights was sharing the opening night billing at Ronnie Scott's club

in October 1959. For a short time he was the house pianist at the club

before realising the ambition that George Shearing had held over a

decade earlier when he, too, moved to America. Unlike other émigrés such

as Dizzy Reece, Thompson quickly made a practical home for himself,

playing a lengthy residency at the famed Hickory House venue in

New York

City, but by the early 1970s he was back in the United Kingdom. A solo

LP recorded live at Ronnie Scott's during this period is long over due

for reissue. Indeed Thompson's career is in need of reappraisal, as, up

until his death in 1986, he was one of the country's best loved and most

assured jazzmen. - Simon Spillett

Having just found, at long last, some reference to that consummate pianist,

Eddie Thompson, I would like to offer some additional and, late, information

on Eddie's later appearances. He was a regular Thursday night performer at the

Anchor Pub in the small West Yorkshire town of Brighouse in the late 70s.He was

a long-time friend of the landlord, an ex-jazz flautist whose first name was

Rod. He was well known for his seamless performances incorporating jazz

standards into a "medley" spot of requests by the audience of around 30 or 40.

He also had a short series on BBC TV, recorded at the Leeds studios for BBC

Bristol , entitled "It Don't Mean A Thing (If It Don't Have That Swing)", again

in the late 70s. In addition, I remember a one night performance by a

re-emerging Marion Williams, another performer for whom there appears to be no

information. Dave van de Gevel Zakynthos Greece

As a frequent

visitor to the Anchor Inn in Brighouse I often used to hear Eddie at

the Thursday sessions. I was also there on the memorable night when

Marion Williams sang. Around the same time Eddie was with Marion at

a cellar club in Stockport & he also accompanied Bud Freeman there.

I think Eddie must have known the chords to every song written in

the 20th Century. He had a great sense

of humour. I remember one night during his residency at the Shay

jazz club in Halifax. There was a lot of noisy chatter from around

the bar. Eddie’s response was to play more & more quietly. At

last one of the listeners could

stand it no longer & shouted to the bar crowd, ‘Be quiet’. Eddie

said, ‘I’m playing as quietly as I can’. I’m so sorry that I

shall never buy him another Glenmorangie.

Ken Austin

Thanks to Ken Austin for confirming my shaky memory

about Eddie's performances at the Anchor Pub in

Brighouse. I did, foolishly, try and test Eddie's

knowledge by asking him to play A Night In Tunisia. With

a wry smile he came out with the classic "You hum it and

I'll play it!". As for Marion Williams, I did find

a reference to her having sung with Dankworth before

being supplanted by Cleo Laine. Has anyone any

information about the tv series that Eddie recorded

which I mentioned before? Nothing on You-Tube so maybe

the BBC just erased it, maybe not. Can Ken clarify

the question as to Rod's surname (landlord of the

Anchor)? He must have been well known on the circuit at

some time as he introduced me to Ronnie Scott and George

Chisholm at a concert in Bridlington in the mid 70's.

Dave van de

Gevel,Zakynthos,Greece.

The landlord at the Anchor Inn was Rod

Marshall who sadly died a few years ago after a long and

debilitating illness. He was never really well after his

return from Korea with

a piece of shrapnel which couldn’t be removed,

He never

lost his sense of humour though. I remember once when a

customer asked him for a packet of Quavers. Rod said,

‘do you want Quavers or demi-semi

Quavers’, ‘I’ll have demi-

semi Quavers’, said the customer so Rod put a packet on

the bar and smashed them with his fist..

Apart from his residency at the Anchor - Eddie played at

various other gigs in the area. He once played a concert

on the stage at Leeds City

Hall accompanied

by a local bass player. Ken Austin

Marion

Williams also sang with the Oscar Rabin band

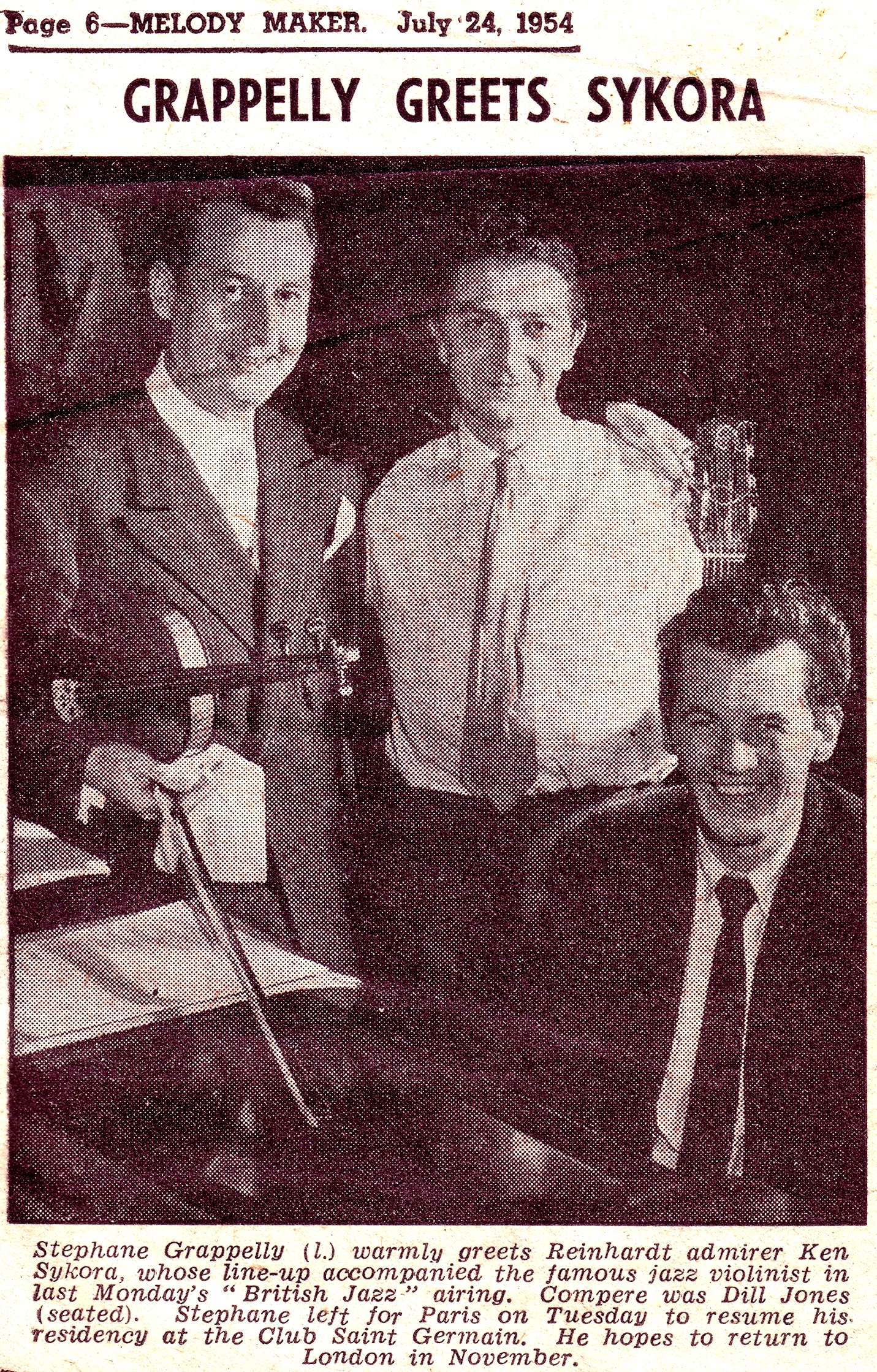

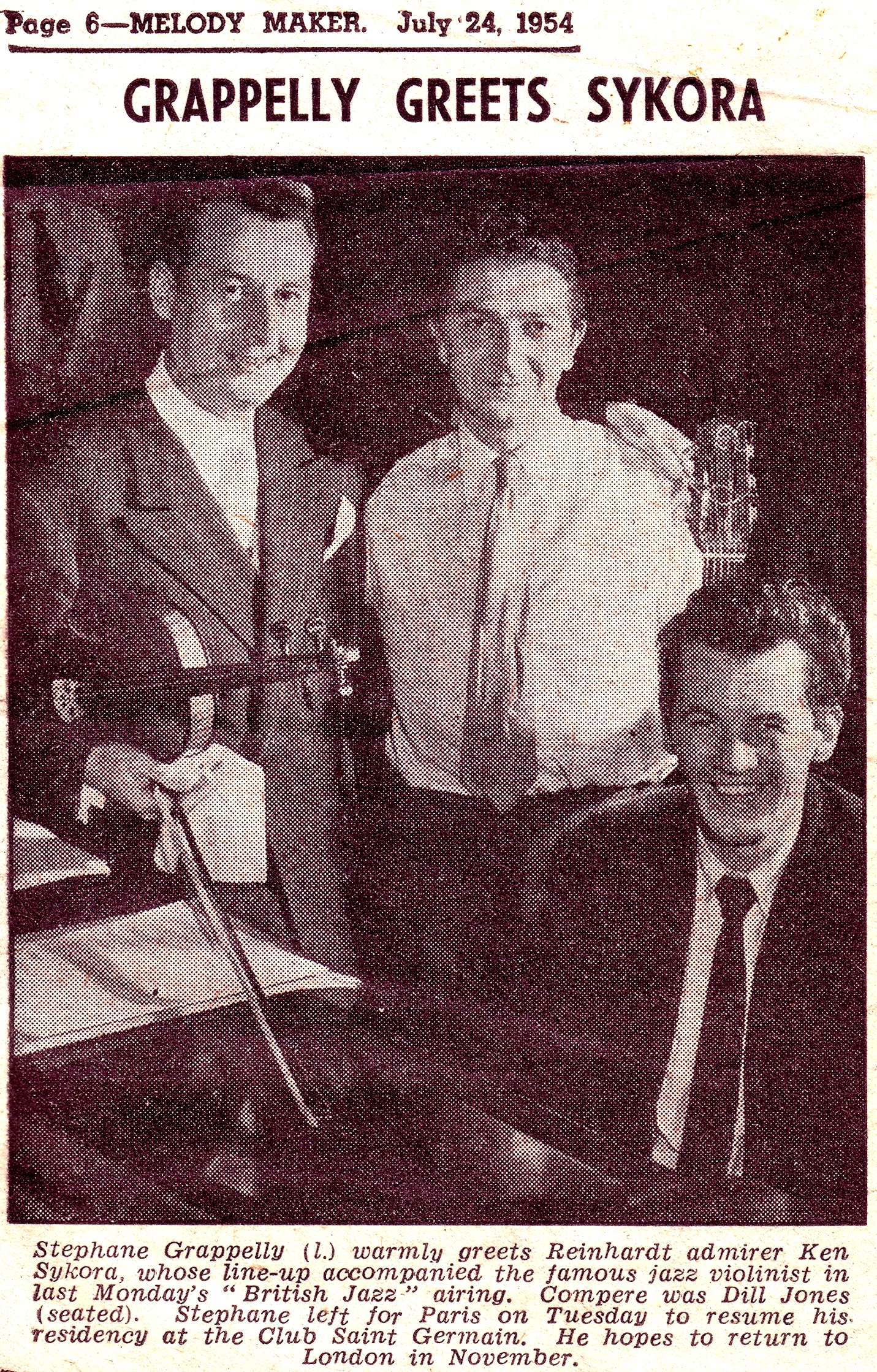

4. Dill

Jones

Dill Jones made a permanent move

to New York in 1961, following a decade as one of London's most

adaptable jazzmen. Jones' wide ranging abilities and enthusiasm are

indicative of how the 'mainstream' of the music had a far more practical

implication in Britain during this era. Before leaving Britain, Jones

had kept pace with all the local bop-based talents - he had played in

Tony Kinsey's Trio, played with Joe Harriott, and had also been a key

member of the Tommy Whittle quintet - but he had also accompanied

Louis

Armstrong. In 1961, at the height of the trad boom, Jones cocked a snook

at convention and led a band of 'modernists', including clarinettist

Vic

Ash and trombonist Keith Christie, and billed itself as the Dixieland

All-Stars, which horrified audiences and critics alike when it played an

all trad programme at London's Flamingo Club. Was this provocation, an

extreme case of hitching a ride on a passing bandwagon, or merely an

indication of Jones' dislike of pigeon holes? When the band made an LP

for Columbia, Jones The Jazz (now as rare hen's teeth), few

original copies were sold to an audience then deeply divided by the trad

versus modern debacle. Jones made few other recordings as a leader while

in Britain. Perhaps his finest was the 1959 EP recorded by the

enterprising Denis Preston at Lansdowne studios, Dill Jones Plus Four.

Original copies are rarities, but anyone lucky enough to own this record

will hear not only Jones' urbane piano style (at the time somewhere

between Teddy Wilson, John Lewis and Tommy Flanagan) exercised on themes

by Duke Jordan and Sonny Rollins, but also the lyrical eloquence of

tenor saxophonist Duncan Lamont. Dill Jones made a permanent move

to New York in 1961, following a decade as one of London's most

adaptable jazzmen. Jones' wide ranging abilities and enthusiasm are

indicative of how the 'mainstream' of the music had a far more practical

implication in Britain during this era. Before leaving Britain, Jones

had kept pace with all the local bop-based talents - he had played in

Tony Kinsey's Trio, played with Joe Harriott, and had also been a key

member of the Tommy Whittle quintet - but he had also accompanied

Louis

Armstrong. In 1961, at the height of the trad boom, Jones cocked a snook

at convention and led a band of 'modernists', including clarinettist

Vic

Ash and trombonist Keith Christie, and billed itself as the Dixieland

All-Stars, which horrified audiences and critics alike when it played an

all trad programme at London's Flamingo Club. Was this provocation, an

extreme case of hitching a ride on a passing bandwagon, or merely an

indication of Jones' dislike of pigeon holes? When the band made an LP

for Columbia, Jones The Jazz (now as rare hen's teeth), few

original copies were sold to an audience then deeply divided by the trad

versus modern debacle. Jones made few other recordings as a leader while

in Britain. Perhaps his finest was the 1959 EP recorded by the

enterprising Denis Preston at Lansdowne studios, Dill Jones Plus Four.

Original copies are rarities, but anyone lucky enough to own this record

will hear not only Jones' urbane piano style (at the time somewhere

between Teddy Wilson, John Lewis and Tommy Flanagan) exercised on themes

by Duke Jordan and Sonny Rollins, but also the lyrical eloquence of

tenor saxophonist Duncan Lamont.

Upon moving to America, Jones did what he did best, once more

befuddling the preconceptions of his critics back home. Having joined

the noisy ranks of the Eddie Condon associated circle in

New York, he

then worked with Jimmy McPartland, Gene Krupa, Bob Wilber and also with

the Dukes of Dixieland. He then settled comfortably into one of the best

mainstream bands of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the

JPJ quartet,

co-headed by saxophonist Budd Johnson and drummer

Oliver Jackson; this

group suffered neglect only because the topsy-turvy world of jazz in

that era was not patient enough to hear music that was not political,

experimental or plugged in. In 1972, Jones recorded a glorious album for

the American Chiaroscuro label, Davenport Blues, a tribute to

Bix

Beiderbecke which affirmed once more the pianist's total lack of regard

for stylistic straight-jackets and which is among his finest recordings.

- by Simon Spillett

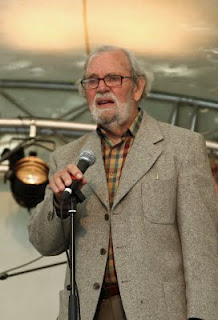

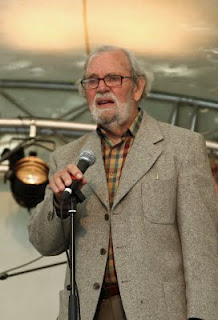

5. Stan

Tracey

The

1960s also saw the long awaited rise to prominence of

Stan Tracey. Although Tracey had

been a professional musician since 1943, it had taken him time to find

his way inside the inner circle of the British modernists, something

borne out of commercial necessity. His early career featured spells with

such unlikely acts as the cod-gypsy Melfi Trio, for whom Stan obliging

returned to his first instrument, the accordion (an instrument he would

play on record with Kenny Baker in the mid-1950s) and by the late

1950s,

despite having made valuable playing connections and recordings with

Ronnie Scott, Jimmy Deuchar and Victor Feldman, Tracey was still having

to earn a commercial crust with the Ted Heath band, wherein his

mischievous sense of humour occasionally threatened to derail the

temperate mood of blandness. The

1960s also saw the long awaited rise to prominence of

Stan Tracey. Although Tracey had

been a professional musician since 1943, it had taken him time to find

his way inside the inner circle of the British modernists, something

borne out of commercial necessity. His early career featured spells with

such unlikely acts as the cod-gypsy Melfi Trio, for whom Stan obliging

returned to his first instrument, the accordion (an instrument he would

play on record with Kenny Baker in the mid-1950s) and by the late

1950s,

despite having made valuable playing connections and recordings with

Ronnie Scott, Jimmy Deuchar and Victor Feldman, Tracey was still having

to earn a commercial crust with the Ted Heath band, wherein his

mischievous sense of humour occasionally threatened to derail the

temperate mood of blandness.

At a time when British jazz pianists were generally trying for the

smooth fluidity of men like Tommy Flanagan, Wynton Kelly and Oscar

Peterson, Tracey represented a distinctly knotty alternative, as can be

heard on his first album as a leader, Showcase, made in 1958 with

Heath band colleagues bassist Johnny Hawksworth and drummer

Ronnie Verrell. The results are by no means mature Tracey, for there are still

more than trace vestiges of his dance band apprenticeship, but the

overall concept is a far different one from merely following a

fashionable star and one can readily recognise the Stan Tracey of today

in this early effort. Tracey had by then in his own words "boiled it

down" to just two major influences, Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk,

and the effect these influences had upon him was to make his style

stark, rhythmically obtuse but assertive, harmonically dense and without

any real recourse to empty technical displays. The iconic album

Little Klunk is the perfect early example of Tracey's skills as they

stood at the dawn of the 1960s, and features only his own compositions,

a trend that the pianist was to follow with unexpected dividends within

a few years.

Such an intractable and stubborn stylist might not have seemed the

ideal choice for the position of house accompanist, but in 1961 Tracey

fell into just such a role at Ronnie Scott's club and over the next

seven years there followed an intense period of musical creativity for

the pianist, alternating work and recordings with his own quartet and

accompanying a bewildering array of visiting American soloists, an

experience he once described as being "like Christmas every night." The

reaction to Tracey was variable. Some, like Sonny Rollins, Roland Kirk,

Jimmy Witherspoon and Zoot Sims were delighted to find a genuine musical

personality at the keyboard and not some fawning non-entity; others were

not. Saxophonists Lucky Thompson and Don Byas were openly hostile, and

Stan Getz had the ego-fuelled nerve to criticise Tracey publicly over

the microphone at the club one night; "bollocks," was Tracey's response.

Tracey had already found something far more useful to do with his

hands than wipe the backsides of the visiting artists at Scott's, but

when a sincere musical dialogue commenced he was ready to throw himself

in with total commitment. "I don't like accompanying twinkling stars,"

he said later, and the same lack of

unnecessary hype and fashion conscious pandering marked his own choice

for regular musical partner when he began to work with tenor saxophonist Bobby

Wellins, another genuine improviser with an unshowy gift. The Tracey-Wellins

partnership was central to one of the greatest triumphs in British jazz, the

1965 recording Under Milk Wood, the story of which has been

documented time and again elsewhere. The follow up album recorded in

1967, With Love From Jazz, has finally been released on CD after

years of being an expensive collectors item on vinyl. If it lacks the

legendary status of its predecessor, it certainly lacks nothing else.

Tracey and Wellins are on peak form, revealing yet another facet of

their hand-in-glove pairing on a loosely connected suite of songs about

love. Tracey had already found something far more useful to do with his

hands than wipe the backsides of the visiting artists at Scott's, but

when a sincere musical dialogue commenced he was ready to throw himself

in with total commitment. "I don't like accompanying twinkling stars,"

he said later, and the same lack of

unnecessary hype and fashion conscious pandering marked his own choice

for regular musical partner when he began to work with tenor saxophonist Bobby

Wellins, another genuine improviser with an unshowy gift. The Tracey-Wellins

partnership was central to one of the greatest triumphs in British jazz, the

1965 recording Under Milk Wood, the story of which has been

documented time and again elsewhere. The follow up album recorded in

1967, With Love From Jazz, has finally been released on CD after

years of being an expensive collectors item on vinyl. If it lacks the

legendary status of its predecessor, it certainly lacks nothing else.

Tracey and Wellins are on peak form, revealing yet another facet of

their hand-in-glove pairing on a loosely connected suite of songs about

love. A period in the jazz wilderness followed in the

1970s, as did some

not entirely convincing collaborations with musicians from the free jazz

scene, but by the 1980s Tracey was back doing what he does best. Indeed,

Tracey is currently going through yet another purple patch and the

renewed interest in his work heralded by a recent BBC4 documentary on

his life and work and by the Jazz Britannia series (although

somewhat cynically received by Stan himself) looks as if it will have

positive ripples. There are plans to reissue several of his classic

albums from the late 1960s and mid-1970s, which include the big band

sessions Alice In Jazzland and The Seven Ages of Man, the

trio album Perspectives, a collaboration with saxophonist Peter

King, Free 'an One, and the much loved album Captain Adventure,

featuring another long-term Tracey sidekick, the tenorist Art Themen.

There can be little doubt that the renaissance of one of this country's

finest jazz talents is both deserved and very welcome. - by Simon

Spillett

6. Lennie

Felix Piano,

b. London, England, d. Dec. 29, 1980. né: Leonard Jacobus Felix.

I was a close

friend of Lennie Felix and when we were together in the Dominican Republic the

year he died we left a cassette tape of him singing songs as well as

accompanying himself on piano. We never got that tape back. I have

been sad ever since that I have only 1 or 2 songs, and the last 4 years of his

life he sang a lot. If you know anyone who has any recordings of Lennie

Felix singing please let me know. He was my greatest friend. Lauren

Liefland, San Diego, California

7. Dave

Lee - any

assistance please?

8.

Brian

Dee arrived

on the London jazz scene at the tail end of the 1950s and quickly

impressed everyone with his adaptation of Wynton

Kelly's Brian

Dee arrived

on the London jazz scene at the tail end of the 1950s and quickly

impressed everyone with his adaptation of Wynton

Kelly's

approach

(including Kelly himself on a tour opposite the Miles Davis Quintet

which Dee made in 1960). This early work can be heard on The Five Of

Us, an album recorded for Tempo by the Jazz Five, co-led by

saxophonists Vic Ash and Harry Klein, and one of the groups that had

sprung up in the wake of the Jazz Couriers. As the years went by, Dee's

playing matured, as is evidenced on several recent CDs: Centurion,

recorded with his quartet featuring saxophonist Alex Garnett, The

Catalyst, a trio session with the redoubtable Dave Green and Clark

Tracey, and a stunning recital of Richard Rodgers' songs with the

saxophonist Duncan Lamont, Happy Talk. He has also become one of

the most respected accompanists on the British jazz scene, working as

effectively with vocalists as with instrumentalists. - by Simon

Spillett approach

(including Kelly himself on a tour opposite the Miles Davis Quintet

which Dee made in 1960). This early work can be heard on The Five Of

Us, an album recorded for Tempo by the Jazz Five, co-led by

saxophonists Vic Ash and Harry Klein, and one of the groups that had

sprung up in the wake of the Jazz Couriers. As the years went by, Dee's

playing matured, as is evidenced on several recent CDs: Centurion,

recorded with his quartet featuring saxophonist Alex Garnett, The

Catalyst, a trio session with the redoubtable Dave Green and Clark

Tracey, and a stunning recital of Richard Rodgers' songs with the

saxophonist Duncan Lamont, Happy Talk. He has also become one of

the most respected accompanists on the British jazz scene, working as

effectively with vocalists as with instrumentalists. - by Simon

Spillett

One of the UK's leading jazz pianists. He first

came to prominence with the opening of the Ronnie Scott Club in 1959.

His international reputation grew and he toured as a member of The Jazz

Five opposite Miles Davis. In 1965 was voted "Melody Maker New Star".

Dee's working experience

as an accompanist of world class vocalists is well known. The list of

jazz stars that he has worked with is endless and includes recording

with Bing Crosby, Johnny Mercer, Peggy Lee and Fred Astaire.

He is still making frequent appearances at Ronnie Scott's and broadcasts

regularly on radio with his own trio.

-

The outstanding

feature of Dee's performance here, is its fleetness of fingering and

cleanness of articulation. Russell Davies, Daily Telegraph

-

Dee's qualities,

delicacy, flexibility, wit and ingenuity soon make themselves

apparent. Dave Gelly The Observer

-

Brian Dee's Trio was

perfect ... amongst the best of our jazz pianists, and probably one

of the best accompanists we have ever had.

Steve Voce Jazz Journal

Eddie Harvey

Eddie Harvey was born in

1925.

After studying the piano classically Eddie Harvey took up the

trombone and became a prime mover in the post war jazz revival.

He became interested in modern jazz in the late 1940’s when he

first played with John Dankworth, Ronnie Scott and other

like-minded young musicians. Eddie Harvey was born in

1925.

After studying the piano classically Eddie Harvey took up the

trombone and became a prime mover in the post war jazz revival.

He became interested in modern jazz in the late 1940’s when he

first played with John Dankworth, Ronnie Scott and other

like-minded young musicians.

Later he was to work with John Dankworth, both in the famous

“Seven” with Cleo Laine and in a number of his Big Bands ,over a

period of many years.

He also played with the American bands of Woody Herman, Maynard

Ferguson and for many years as a pianist with Humphrey Lyttelton’s band.

Eddie Harvey is also well known as a jazz composer and arranger,

having written music for radio, TV, film and theatre over the

years. He recently wrote music for Cleo Laine’s album singing

with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. This summer his music was

heard in a series of programmes for Channel 4 TV.

He has also been involved in education as a tutor at the City

Literary Institute, Head of Brass at Haileybury College and

Director of the Hertfordshire Youth Jazz Ensemble, as well as

free-lance director/tutor for numerous Summer Music courses,

schools and PGCE Courses. Eddie Harvey is currently the Head of

Jazz Studies at the London College of Music, where he also

conducts the LCMM Big Band and Jazztet. These units have

appeared with guest artists including John Dankworth, Peter King

and John Surman; and have recently performed on the London and

Ealing Jazz festivals; and in concert at the Queen Elizabeth

Hall and the Wembley Conference Centre.

He has been involved as adviser and composer to the Associated

Board for many years.

|

Dudley

Stuart John Moore was born in Dagenham, East London on April

19th, 1935. He was taught the piano by his parents when just

eight and took up the violin aged eleven. Young Dudley also

attended the Guildhall School Of Music every Saturday

morning, learning the history and appreciation of music as

well as violin lessons. Whilst singing in the choir in his

local Dagenham church, he was persuaded to play the church

organ and further persuaded to apply for an organ

scholarship to study music at University. Dudley was

successful, attained the scholarship and entered Oxford

University, graduating aged 22 with BA degrees in both Music

and Composition from Magdalen College.

Dudley

Stuart John Moore was born in Dagenham, East London on April

19th, 1935. He was taught the piano by his parents when just

eight and took up the violin aged eleven. Young Dudley also

attended the Guildhall School Of Music every Saturday

morning, learning the history and appreciation of music as

well as violin lessons. Whilst singing in the choir in his

local Dagenham church, he was persuaded to play the church

organ and further persuaded to apply for an organ

scholarship to study music at University. Dudley was

successful, attained the scholarship and entered Oxford

University, graduating aged 22 with BA degrees in both Music

and Composition from Magdalen College.

Dill Jones made a permanent move

to New York in 1961, following a decade as one of London's most

adaptable jazzmen. Jones' wide ranging abilities and enthusiasm are

indicative of how the 'mainstream' of the music had a far more practical

implication in Britain during this era. Before leaving Britain, Jones

had kept pace with all the local bop-based talents - he had played in

Tony Kinsey's Trio, played with Joe Harriott, and had also been a key

member of the Tommy Whittle quintet - but he had also accompanied

Louis

Armstrong. In 1961, at the height of the trad boom, Jones cocked a snook

at convention and led a band of 'modernists', including clarinettist

Vic

Ash and trombonist Keith Christie, and billed itself as the Dixieland

All-Stars, which horrified audiences and critics alike when it played an

all trad programme at London's Flamingo Club. Was this provocation, an

extreme case of hitching a ride on a passing bandwagon, or merely an

indication of Jones' dislike of pigeon holes? When the band made an LP

for Columbia, Jones The Jazz (now as rare hen's teeth), few

original copies were sold to an audience then deeply divided by the trad

versus modern debacle. Jones made few other recordings as a leader while

in Britain. Perhaps his finest was the 1959 EP recorded by the

enterprising Denis Preston at Lansdowne studios, Dill Jones Plus Four.

Original copies are rarities, but anyone lucky enough to own this record

will hear not only Jones' urbane piano style (at the time somewhere

between Teddy Wilson, John Lewis and Tommy Flanagan) exercised on themes

by Duke Jordan and Sonny Rollins, but also the lyrical eloquence of

tenor saxophonist Duncan Lamont.

Dill Jones made a permanent move

to New York in 1961, following a decade as one of London's most

adaptable jazzmen. Jones' wide ranging abilities and enthusiasm are

indicative of how the 'mainstream' of the music had a far more practical

implication in Britain during this era. Before leaving Britain, Jones

had kept pace with all the local bop-based talents - he had played in

Tony Kinsey's Trio, played with Joe Harriott, and had also been a key

member of the Tommy Whittle quintet - but he had also accompanied

Louis

Armstrong. In 1961, at the height of the trad boom, Jones cocked a snook

at convention and led a band of 'modernists', including clarinettist

Vic

Ash and trombonist Keith Christie, and billed itself as the Dixieland

All-Stars, which horrified audiences and critics alike when it played an

all trad programme at London's Flamingo Club. Was this provocation, an

extreme case of hitching a ride on a passing bandwagon, or merely an

indication of Jones' dislike of pigeon holes? When the band made an LP

for Columbia, Jones The Jazz (now as rare hen's teeth), few

original copies were sold to an audience then deeply divided by the trad

versus modern debacle. Jones made few other recordings as a leader while

in Britain. Perhaps his finest was the 1959 EP recorded by the

enterprising Denis Preston at Lansdowne studios, Dill Jones Plus Four.

Original copies are rarities, but anyone lucky enough to own this record

will hear not only Jones' urbane piano style (at the time somewhere

between Teddy Wilson, John Lewis and Tommy Flanagan) exercised on themes

by Duke Jordan and Sonny Rollins, but also the lyrical eloquence of

tenor saxophonist Duncan Lamont. The

1960s also saw the long awaited rise to prominence of

Stan Tracey. Although Tracey had

been a professional musician since 1943, it had taken him time to find

his way inside the inner circle of the British modernists, something

borne out of commercial necessity. His early career featured spells with

such unlikely acts as the cod-gypsy Melfi Trio, for whom Stan obliging

returned to his first instrument, the accordion (an instrument he would

play on record with Kenny Baker in the mid-1950s) and by the late

1950s,

despite having made valuable playing connections and recordings with

Ronnie Scott, Jimmy Deuchar and Victor Feldman, Tracey was still having

to earn a commercial crust with the Ted Heath band, wherein his

mischievous sense of humour occasionally threatened to derail the

temperate mood of blandness.

The

1960s also saw the long awaited rise to prominence of

Stan Tracey. Although Tracey had

been a professional musician since 1943, it had taken him time to find

his way inside the inner circle of the British modernists, something

borne out of commercial necessity. His early career featured spells with

such unlikely acts as the cod-gypsy Melfi Trio, for whom Stan obliging

returned to his first instrument, the accordion (an instrument he would

play on record with Kenny Baker in the mid-1950s) and by the late

1950s,

despite having made valuable playing connections and recordings with

Ronnie Scott, Jimmy Deuchar and Victor Feldman, Tracey was still having

to earn a commercial crust with the Ted Heath band, wherein his

mischievous sense of humour occasionally threatened to derail the

temperate mood of blandness.

Brian

Dee

Brian

Dee

Eddie Harvey was born in

1925.

After studying the piano classically Eddie Harvey took up the

trombone and became a prime mover in the post war jazz revival.

He became interested in modern jazz in the late 1940’s when he

first played with John Dankworth, Ronnie Scott and other

like-minded young musicians.

Eddie Harvey was born in

1925.

After studying the piano classically Eddie Harvey took up the

trombone and became a prime mover in the post war jazz revival.

He became interested in modern jazz in the late 1940’s when he

first played with John Dankworth, Ronnie Scott and other

like-minded young musicians.